The trial of

Jose Padilla, one-time accused "dirty bomber," appears likely to be delayed yet again. The

Associated Press reported that it has been ruled that Padilla, an American citizen designated an "enemy combatant" by

President Bush, and subsequently held in solitary confinement without charge and without access to counsel for three and a half years, must undergo a competency evaluation. From the AP story:

A psychiatrist and clinical psychologist who evaluated Padilla in September and October at his attorneys' request concluded independently that he has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and is unable to help his defense lawyers prepare adequately for trial.

"His reasoning is clearly impaired and paranoid tendencies are evident throughout the interviews," the psychiatrist, Dr. Angela Hegarty, said in a formal assessment filed late Wednesday in federal court. "Facial tics are prominent when he becomes distressed. He appears hypervigilant at times."

Padilla, a 36-year-old U.S. citizen, is scheduled to stand trial January 22 along with two others in a terrorism support case. He claims he was tortured during his years in military custody at a naval brig in Charleston, SC. He has asked U.S. District Judge Marcia Cooke to dismiss the Miami charges against him because of "outrageous government conduct" during his detention and interrogations.

The circumstances of Jose Padilla, about whom I have written on several occasions (in chronological order:

The Constitution as Inconvenience,

The Abyss Stares Back,

The Disappeared) are terrifying, shameful and sad in the extreme. Although he may indeed be guilty of some or all of the charges that have been leveled against him since his arrest and imprisonment, it is a sobering fact that no matter what the outcome of his ordeal, his day in court only came about because of relentless outside pressure. Absent that pressure, George W. Bush was content to incarcerate a U.S. citizen indefinitely and without trial.

Some legal scholars believe that

the government's case against Padilla is weak, and that he will either be convicted of a relatively minor charge or acquitted altogether. While there are those who might find comfort in this, telling themselves that "the system works," Mr. Padilla will still have undergone

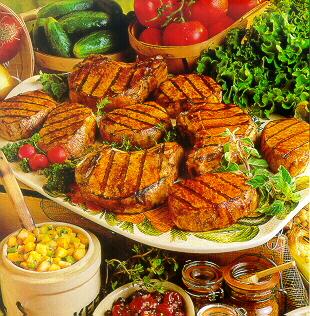

extremely harsh treatment - including sensory deprivation, as pictured above - the effects of which he will have to deal with for the rest of his life.

Of paramount importance - and what needs to be stated as clearly as possible and repeated often - is the fact that the case of Jose Padilla is in no way a one-time "mistake". Although it appears that many Americans are content to see

foreigners in our custody denied fundamental rights, letting them suffer

longterm solitary confinement, force-feeding and a complete lack of legal redress, additional accounts of U.S. citizens receiving similar treatment will perhaps generate the shock and anger that are crucial to reversing the tide of anti-civil liberties excesses from the Bush Administration.

The

New York Times reported on just such a case this weekend, and while there will almost certainly be those who cling to the belief that Jose Padilla's troubled past and poor choices are ample cause for his unconstitutional imprisonment, it will be much harder to muster similar justification about

Donald Vance. Vance, a 29-year-old Navy veteran from Chicago working in

Iraq as a security contractor, was also passing information to the

FBI as a whistleblower. He had stumbled upon suspicious activities at the security firm where he was employed - including what he believed to be trade in illegal weapons - but when U.S. soldiers raided the company at his urging, Vance and a fellow American contractor, Nathan Ertel, were detained as suspects.

According to official statements, the military was unaware that Mr. Vance was actually their confidential informer, and, giving him a taste of what foreign-born prisoners endure for years, disappeared him into solitary confinement for over three months without access to an attorney or contact with the outside world. From the

Times story:

Mr. Vance said he began seeking help even before his cell door closed for the first time. “They took off my blindfold and earmuffs and told me to stand in a corner, where they cut off the zip ties, and told me to continue looking straight forward and as I’m doing this, I’m asking for an attorney,” he said. “ ‘I want an attorney now,’ I said, and they said, ‘Someone will be here to see you.’ ”

Instead, they were given six-digit ID numbers. The guards shortened Mr. Vance’s into something of a nickname: “343.” And the routine began.

Bread and powdered drink for breakfast and sometimes a piece of fruit. Rice and chicken for lunch and dinner. Their cells had no sinks. The showers were irregular. They got 60 minutes in the recreation yard at night, without other detainees.

Five times in the first week, guards shackled the prisoners’ hands and feet, covered their eyes, placed towels over their heads and put them in wheelchairs to be pushed to a room with a carpeted ceiling and walls. There they were questioned by an array of officials who, they said they were told, represented the FBI, the CIA, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) ...

... The two men slept in their 9-by-9-foot cells on concrete slabs, with worn three-inch foam mats. With the fluorescent lights on and the temperature in the 50s, Mr. Vance said, “I paced myself to sleep, walking until I couldn’t anymore. I broke the straps on two pair of flip-flops.”

Granted hearings because of their American citizenship - something to which foreign-born prisoners have no guarantee - Nathan Ertel pleaded with the review board: “Please, I’m out of my mind. I haven’t slept. I’m not eating. I’m terrified." Mr. Vance, meanwhile, asked "Does my family know I’m alive?" to which he was given the response, "I don't know." Two weeks into his detention, Vance was allowed to call his fiancée in Chicago, who told him she thought he had been killed. Mr. Vance begged her to talk to anyone she could, and to bring as much pressure to bear as possible. That was the last time he spoke to her during his captivity.

Nathan Ertel was released relatively quickly, but for some reason which has yet to be explained, the military continued to label Mr. Vance a "threat," despite having cleared up the issue of his whistleblower status. Mysteriously, after an "additional review" months later, he was released and returned to the United States. Ashamed, depressed and paranoid, Mr. Vance is now preparing to sue former

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld for violating his constitutional rights.

Again, to be clear: Charles Vance, an American citizen and Navy veteran, was interned for 97 days without access to the outside world and without independent judicial review. His family had no idea what had happened to him - or whether he was alive or dead - and it is only because the military deigned to release him - with implied threats that he'd better keep his mouth shut - that he is today a free man. Mr. Vance's ordeal is what happens when

habeas corpus, a fundamental human right in Western civilization for more than 900 years

becomes optional. It is what happens when

checks and balances fall by the wayside and we do not hold our leaders to account.

To be sure, the human desire for security is a natural one, but it is vital to recognize that the

founders of the United States wrote the

Constitution with the express purpose of subordinating security to freedom. Today, as there have been throughout our history, there are

men who ask us to surrender our freedoms, to place our fates in their hands, and to trust their benign despotism. Their rallying cry is that "

the Constitution is not a suicide pact," ignoring the fact that the

Declaration of Independence concludes "And for the support of this Declaration ... we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor," a statement that freedom is worth any price, if ever there was one.

The notion that individual liberty is more important than the convenient exercise of police power is fundamental to our national character. It is what has defined us as a nation of laws rather than men, and it is what shaped the admiration for the United States held by a good portion of the world's population in the post-War era. It is no coincidence then, that as we have abandoned our principles through stupidity and arrogance manifested in the invasion of Iraq,

Guantanamo Bay,

Abu Ghraib, and the

Military Commissions Act, we have seen our

standing plummet in the eyes of the world.

As Donald Vance puts it:

“Even Saddam Hussein had more legal counsel than I ever had. While we were detained, we wrote a letter to the camp commandant stating that the same democratic ideals we are trying to instill in the fledgling democratic country of Iraq, from simple due process to the Magna Carta, we are absolutely, positively refusing to follow ourselves.”

Our claims to fairness are belied by the

kangaroo courts we have established to "try" our captives, and the cases of men like Padilla and Donald Vance amply demonstrate that we can no longer even claim to treat our own citizens as we would have others treat theirs. In the eyes of the world,

we are greatly diminished, and deservedly so. We are - after all - what we do and not merely what we say, and by that measure, our leaders have made us little more than a nation of hypocrites.

[For more on Donald Vance, click on the radio icon for the podcast of a December 19th interview on NPR's On Point with Tom Ashbrook.]