Today, the Crescent City is suffering what may be its worst affordable housing crisis since the Civil War. With tens of thousands of homes demolished by the storm or made uninhabitable, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) reports that the rental rate in New Orleans is at 100 percent. Eighteen months after Katrina made landfall in The Big Easy, and despite an exodus that has seen the population of Louisiana's biggest city roughly halved, there isn't close to enough housing to go around, especially for the poorest residents.

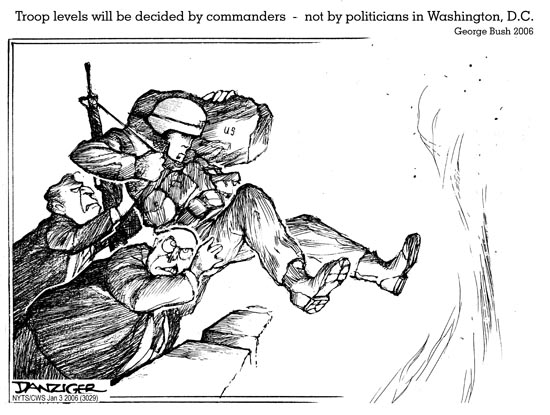

Given the urgency of the situation, it would not be unreasonable to expect that reconstruction efforts would focus on providing housing in the fastest, most cost-effective manner. As has so often happened in the 6 years since George W. Bush claimed the White House however, the reasonable expectation is not the case. Instead, HUD has announced plans to demolish more than 4,500 St. Bernard Parish public housing apartments in the B.W. Cooper, C.J. Peete, St. Bernard and Lafitte developments, and replace them with approximately 800 mixed income units, of which only half would be targeted to lower income families. In other words, despite a severe housing shortage, the federal government is moving forward with plans to supply less than one-eleventh of the units it aims to raze.

This would be at least somewhat defensible if the buildings in question were unsafe, but that is not the case. John Fernandez, an Associate Professor of Building Technology in the Deptartment of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), conducted an assessment of the affected public housing units, and made the following statement:

My inspection and assessment found that no structural damage was found that would reasonably warrant any cost-effective building demolitions. While I found a range of Katrina related damage to these buildings, I did not find any conditions in which the integrity of the structure and exterior envelope of the buildings or the interior conditions of residential units themselves could not be brought to safe and livable conditions with relatively minor investment.

I also found that there was only a minimum use of cellulose-based materials (wood in rough openings and baseboards and paper in the rare use of gypsum wall board for example). This lack of organic material significantly aided in the very low incidence of moisture retention in the walls and floors of the buildings....

[D]emolition of any of the buildings of these four projects is not supported by the evidence of the survey, replacement of these buildings with contemporary construction would yield buildings of lower quality and shorter lifetime duration, the original construction methods and materials of these projects are far superior in their resistance to hurricane conditions than typical new construction, and with renovation and regular maintenance, the lifetimes of the buildings in all four projects promise decades of continued service that may be extended indefinitely.

Worse, documents from the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) show that repairs on the affected housing developments - and even wholesale rennovation - could be accomplished for a fraction of the cost of demolition and the subsequent building of fewer units. Bill Quigley, a law professor and attorney representing residents of the apartments scheduled for demolition, quotes the HANO documents as follows:

... Lafitte could be repaired for $20 million - even completely overhauled for $85 million - while the estimate for demolishing and rebuilding many fewer units will cost more than $100 million. St. Bernard could be repaired for $41 million or substantially modernized for $130 million, while demolishing and rebuilding fewer units will cost $197 million. B.W. Cooper could be substantially renovated for $135 million, compared to $221 million to demolish and rebuild fewer units. C.J. Peete's own insurance company reported that it would take less than $5,000 each to repair the C.J. Peete apartments.

Past experience however, has made low-income residents of Louisiana public housing wary of such claims, and their anxiety is justified by recent history at the St. Thomas complex. St. Thomas, which originally housed around 1,500 families, was demolished in 2002. To date however, only 296 replacement units have been constructed and just 122 of them are low-income housing. Taking this as their cue, residents and activists have recently re-occupied the housing complexes targeted for demolition - despite lacking both power and water - and now, HUD and the New Orleans housing authority are suing to have them removed.

Tragically, there appears to be little appetite at the federal level to ensure fairness in reconstruction. Senator Joseph Lieberman, who chairs the Senate Homeland Security Committee as an Independent, campaigned for re-election in 2006 partly on the strength of calls to pursue an investigation into the failure of the federal response to Katrina. After a bitterly contested race which saw him lose the Connecticut Democratic primary, Lieberman has since said he may vote Republican in the 2008 presidential election, and his spokesperson has publicly stated that he will not pursue further inquiry into missteps surrounding the Bush Administration response to the hurricane.

While no allegations of criminal wrongdoing have been made, past actions at St. Thomas and the general foot-dragging that seems to be continuing in New Orleans in the wake of Katrina make it difficult to discount contentions that race and class are playing a role in decisions about public housing. The apartment complexes in question were undoubtedly poor and crime-ridden, but the fact remains that rebuilding insufficient housing will further displace thousands of people who have already been homeless for more than a year.

HUD spokesman Jereon Brown may genuinely believe that "People deserve better than this," but when he says, "If they could just be patient. A mixed-income neighborhood can better attract businesses and better schools," he reveals an arrogance it is difficult to imagine being applied to more affluent elements of Louisiana society. Judith Browne-Dianis, co-director of the Advancement Project, a Washington-based civil rights and racial justice group representing tenants seeking to reclaim their apartments, thinks that's the case, and makes a credible claim when she notes:

It's definitely about race and class. If you look at what happened after Hurricane Katrina, the people who were residents of public housing were the people who were left behind at the Superdome and Convention Center, and now they are the same people who are being locked out.As Jacquelyn Marshall, a former resident at C.J. Peete put it:

We are not against the redevelopment of public housing. We are against the process. I'm not for tearing down something that's livable when it will result in thousands of families being homeless. They need to start renovating before they demolish.That's pretty hard to argue.